Did you ever run, jump or kick and feel a sudden sharp pain in the front of your thigh? It’s probably your Rectus Femoris (RF) – part of the group of muscles known as quads – and a muscle frequently strained through sudden or explosive movement.

The RF is what’s known as a biarticular muscle, meaning it passes over two joints. In this case, it’s the hip and knee and the RF’s job is to extend the knee straight and also flex the hip. With a high proportion of what we call type II muscle fibres, it’s one of the body’s most powerful muscles.

As such, at W5, we see RF injuries most commonly in speed runners, kick boxers or people who play sports like football, basketball and rugby.

RF injuries are really common. In the 2008 Olympics held in Beijing, thigh strains were the second most frequently occurring injury, only beaten by ankle sprains. They equate to 50% of injuries which happen in the muscle/tendon/bone unit in elite soccer players (Lee et al, 2012).

Causes of RF strains

Although RF strains can happen to pretty much anyone, there are a number of things that can increase the likelihood of you experiencing this kind of injury.

Risk factors have been categorised into:

1. Intrinsic, which includes:

- Age

- Previous injury

- Gender (men are the most likely to suffer from this kind of injury)

- Decreased height

- Increased weight

- Lack of flexibility

- Lack of eccentric strength (i.e. when going down stairs and having difficulty controlling your decent due to quads struggling to resist your weight)

- Type II muscle fibre – added to the list by Balius et al in 2009

and,

2. Extrinsic, meaning external factors such as:

- Sports played on hard ground (i.e. 5-a-side football)

- Insufficient warm up, and;

- Poor conditioning, which were both added as further risk factors on the extrinsic list by Gyftopoulos et al in 2008.

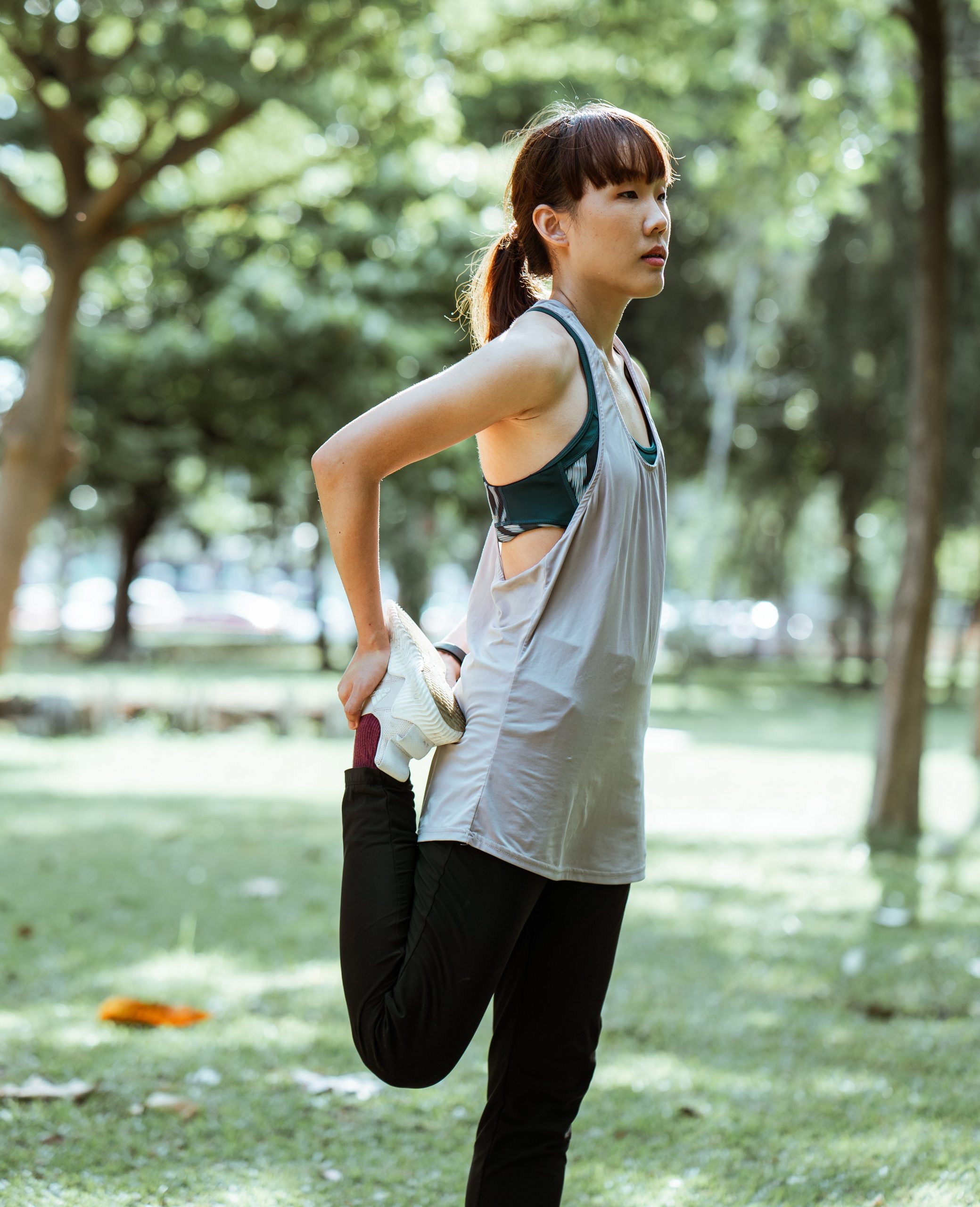

This photograph provides an example of the Rectus Femoris under stretch across the hip and knee joint. Lengthening this muscle under tension is thought to overload the tendon as the athlete kicks the ball, or carries out similar movements when sprinting and jumping.

Assessment

The science bit? Well, many have postulated about the biomechanics of RF injuries. Soderberg suggested in 1983 that it’s a mismatch between a compliant tissue (muscle) and a stiff tissue (tendon) that leads to injury. Although a full discussion of the biomechanics are far beyond the realms of this blog…

What you’re probably more interested in is how we may assess an RF problem when you come to clinic and the answer is…ultrasound or MRI.

Ultrasonography’s traditionally been used to only diagnose muscle strain injuries. Today’s advances in ultrasound mean that we can now define the exact location, size, length and width of the injury, making treatments (such as shockwave therapy) more accurate and a prognosis and recovery time more predictable.